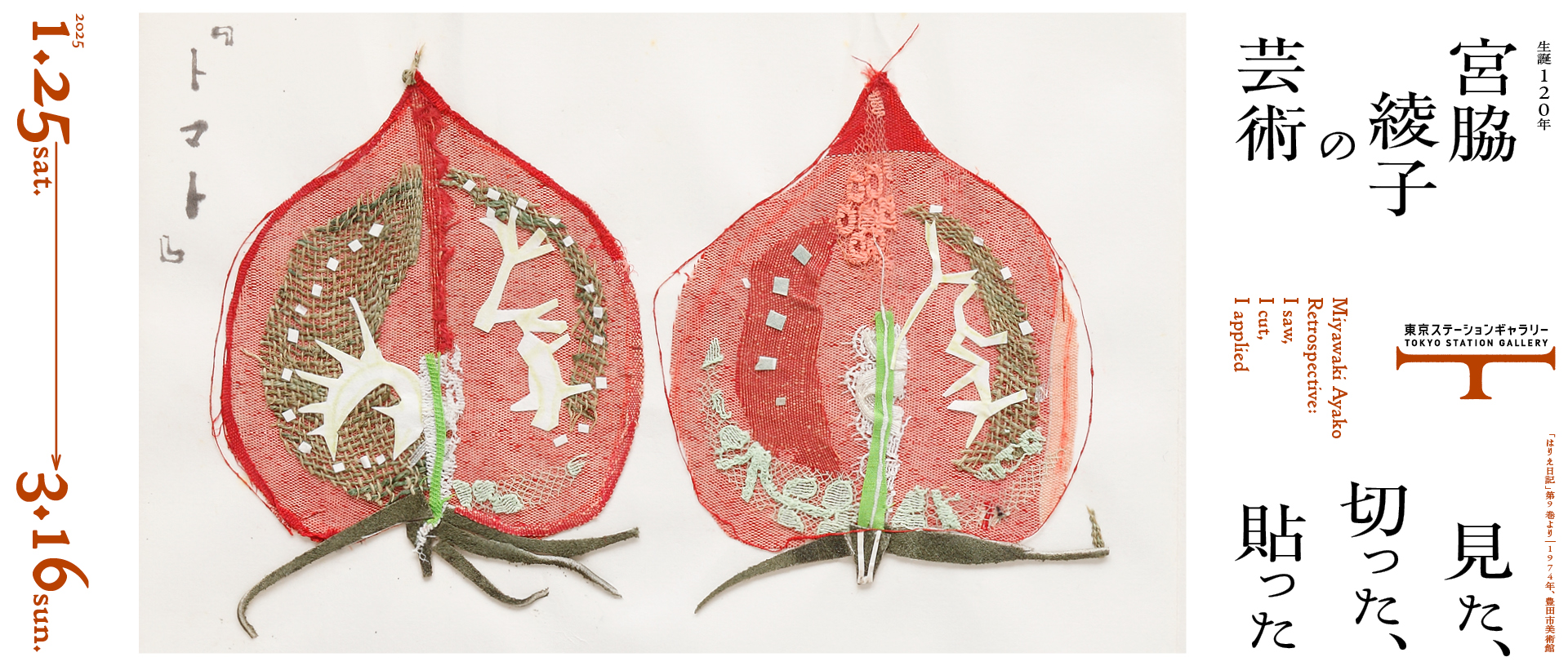

Miyawaki Ayako Retrospective: I saw, I cut, I applied

Saturday, January 25 - Sunday, March 16, 2025

- Closed

- Mondays (except February 24, March 10), February 25

- Hours

- 10:00 am to 6:00 pm (8:00 pm on Fridays)

Last admission is 30 minutes before closing time.

Exhibition Overview

Miyawaki Ayako (1905-1995) has continued to create beautiful and intimate works on fabric and paper, representing familiar objects. Her work has been categorized as appliqué, collage, and handicraft, but its rich expressiveness clearly takes it beyond the technique’s traditional framework. Her motifs were things she dealt with every day as a housewife, such as vegetables and fish in the kitchen. She thoroughly observes her subject, by cutting it to reveal the cross section or disassembling to confirm its structure. Through these tireless research, her appliqués are excellently formed; but they also brilliantly express the radiance of life, supported by a keen and delicate sense of design and color.

This exhibition considers Miyawaki Ayako as an outstanding plastic artist within the context of fine art and categorizes and arranges more than 150 of her works and materials into eight chapters based on their plastic characteristics. By applying the vocabulary of art-historical study to her achievement, it attempts to shed new light on a rare talent.

What you create on your own is truly precious.

―Miyawaki Ayako, Watashi no sōsaku appurike: ai ni miserarete [My creative appliqué: fascinated by indigo]

Sections

Observation and realism

Miyawaki Ayako placed great importance on looking. Her creative process began by thoroughly observing something, eyes focused not only on the shape and color of her subject but also the individual parts and fine details of its structure. It is not unusual to find in her sketchbooks page after page given over to the same motif drawn time and again. Her method relied on relentless observation. She would sometimes go to the trouble of separating the leaves from a plant or the calyx from a flower to study how they were attached. If her family received a parcel of prawns or crabs to eat, they often had to wait until after she completed her examination before cooking them. Her observant eye produced works remarkable for their realism, even though sewing fabric is a far more cumbersome process than drawing.

Cross sections and multiple perspectives

Cross sections of fruit and vegetables were among Miyawaki’s favorite subjects. Pumpkins, wax gourds, watermelons, onions, and green peppers—there are countless examples of works depicting foodstuffs cut in half. Often it seems after chopping ingredients during meal preparation, she was struck by the beauty of their open faces. She also represented animals, such as fish and birds, in paired images from front and back or juxtaposed them viewed from different angles. These approaches suggest a desire to comprehend everything about the subject. The comparison may seem far-fetched, but in this respect, she shared the instinct of many famous artists with inquiring minds, such as Leonardo da Vinci, who dissected human bodies to understand the structure, or Rembrandt, who painted the flayed carcass of a bullock.

Diversity

Keenly observant and inquisitive to the core, Miyawaki once wrote: “No two things that God has created are the same.” More than usual, she must have been intrigued by the diversity of the natural world, which breathes in her works. Each of her bamboo shoots, a much-repeated motif, is composed of different fabrics and has a different look. Miyawaki’s eye never misses the subtle differences in the furled stems and fronds of bracken and royal fern shoots, the colors and shapes of dried squid and dried persimmons, or the unique appearance of each individual bud of an udo (Japanese spikenard). No doubt her expression of diversity required acute observation and an insatiable curiosity; but, just as certainly, it derived from her daily life as a housewife, handling foodstuffs.

Utilizing material

Miyawaki selected her materials carefully. She would often browse in shops and markets, searching for the antique cloth she preferred. She also obtained secondhand cloth from dealers and received various types of fabrics from her many acquaintances. She once wrote that, because of her deprived childhood and the influence of her mother-in-law, someone who took good care of things, she could never discard a remnant. She was interested not only in precious antique cloth but all kinds of material, from lace and printed fabrics to faded towels, old judo uniforms, used cloth coffee filters, and even the cotton-wick cores of oil stoves. Utilizing these diverse resources, she skillfully simulated the textures of her motifs, along with their subtle expressions such as shadows and wrinkles.

Utilizing patterns

Miyawaki used cloths with all kinds of patterns and designs in her works—from traditional kisshō (auspicious) motifs to indigo-dyed stripes and plaid patterns, from the bold and colorful patterns of traditional satsuki-nobori streamers to printed floral and shōchikubai (pine-bamboo-plum) motifs. It was not uncommon for her to cleverly simulate reality : a dragon pattern expressing the spiky appearance of a stonefish, the geometric pattern of a shirushi-banten (livery with trademark) mimicking the sheath of a bamboo shoot, or sharkskin patterns conjuring up a starry sky—what can only be described as “Miyawaki magic.” This approach may be considered a form of mitate (comparison, likening), a technique used in traditional Japanese art. Just as lines in the white sand of a Japanese garden mimic the movement of water, so patterns in her works echo various other things.

Playing with patterns

As well as making skillful use of fabric patterns to achieve realism, Miyawaki also created bold forms that exploit interesting patterns for their own sake. She has said that she sometimes contemplated what she should make while looking at patterns; for her, they were not just the building blocks of a work but a source of inspiration. Many of her creations depart from realism and play freely with patterns—such as the sea bream with crane and turtle motifs on its back or the row of sword beans that look like neckties with various designs. By introducing a pattern with no obvious connection to the chosen motif, an unexpected encounter can be produced. These formulations reveal her to be an artist not only intent on realism.

Effective use of lines

Appliqué is generally created by sewing fabric onto fabric. In other words, the subject is treated as a series of planes, which are built up to make the form. While the omission of details may help the artist to grasp the essential form of a subject, the technique is not well suited to intricate expression. Miyawaki, however, widened the expressive range of appliqué by adding string lines and threads to her works. Importantly, this allowed her to depict fine details such as plant roots and thin stalks, elements that fascinated her. In the same way, she could render the shape of a transparent glass container. Nothing is more suitable for observing—or expressing—new shoots and growing roots than a glass container filled with water.

Orientation toward design

Since appliqué is based on cutting out shapes from cloth, details need to be omitted in large part; essentially, it is a technique that involves simplification. While some of Miyawaki’s works attempt to express nuances of detail, by using materials such as thread, lace, and nets, quite a number emphasize simplicity. In addition to simplifying their subject, these works sometimes feature deformations and repetition of motifs. If the principle of design relies not on making a display of originality or merely adding decorative details, but on observing nature, extracting its essential shapes, and arranging them in a certain order, then Miyawaki’s works can be said to demonstrate it remarkably well.

Information

- Admission Fees

-

Adults: 1,300 (1,100) yen, High school and University students: 1,100 (900) yen

Junior high-school students and younger: Free- *Prices in ( ) indicate the advance ticket prices.

- *Advance tickets are available online from December 1, 2024 to January 24, 2025.

- *Persons with disability certificate or similar receive a 200 yen discount, and one accompanying helper is admitted free.

- *Students must present student ID upon entrance to the museum.

- Ticketing

-

Where to Buy Tickets:

- ・At Online

- ・At the Entrance of Tokyo Station Gallery

- *Please purchase tickets online in advance to ensure smooth entry.

- *Please purchase tickets at the museum if you wish to receive a discount by presenting a coupon or membership card. Please note that you may be asked to wait to enter during congested times.

- Organised by

- Tokyo Station Gallery [East Japan Railway Culture Foundation]

- With the special cooperation of

- Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

- Sponsored by

- T&D Insurance Group